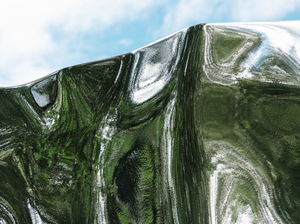

“Blue”

by Marianne Heske

Blue

- Unveiled 16th august 2023

- Materials Painted bronze

- Dimensions 5 x 2.5 x 3m

- Artist Marianne Heske

- Where Show on map

Marianne Heske has been working as an artist for over 40 years and is considered a pioneering figure in Norwegian conceptual art. She works with graphic techniques, photography, silk screen printing, collage, installation, and sculpture. Blue was unveiled on August 17, 2023. The work, along with its accompanying amphitheater, is located outside The Twist on the north side of the Randselva River.

Blue is a continuation of Heske's work with the doll's head, a recurring motif in her art since the 1970s. The sculpture, which cries at irregular intervals, will be Heske's second artwork in the sculpture park joining Homage to Leo the Lion (2006). Blue is located at the exit of The Twist on the north side of the river Randselva, and incorporates an amphitheater in the surrounding area.

When Marianne Heske's latest work is unveiled—a monumental doll's head painted and entitled Blue—it will be over fifty years since the humanoid object made its entry into Heske's artistic universe. The story is as well-known as the doll's head is iconic: As a young art student in Paris in the early 1970s, strolling through one of the city's flea markets, Heske was drawn to a box filled to the brim with tiny doll’s heads. There they were, mass-produced and almost identical: designed sometime in the 1920s for the little girls of that era, delicately crafted in papier-mâché, but fifty years later discarded and without bodies. However, after going home with the young artist the doll's head was given a new lease of life and has since then appeared in several of Heske's most prominent works. We find it in video and photo works, in prints, collages and performances, and as sculptures in different sizes and materials. Blue, as an exact formal replica of the original doll’s head, is the latest addition to the series of hundreds of doll’s heads created since 1971.

Beyond the form, however, there are several things that distinguish Blue from its Parisian predecessor. Most striking is probably the format: The head, which is cast in bronze, is about seventy times larger than the original from the flea market, and despite its explicitly anonymous features, it therefore appears massive and authoritative. The dimensions of the work inevitably bring to mind Head N.N. (2014), one of Heske’s most well-known doll’s heads due to its location in Torshovdalen. Also, an amphitheatre has been built around Blue that invites visitors to sit down and watch the doll’s head perform its silent message. But where the aforementioned skull is characterized by a phrenological map and has a title that insists on the absence of identity (the abbreviation N.N., nomen nescio, is Latin for "I don't know the name"), the title Blue points to another prominent feature of the work, namely the clear, royal blue colour covering the surface.

Discreetly located in one of the sculpture park's green groves, on the edge of the Randselva river, the consequence of the use of colour and the large format is that the work stands out as a foreign object in the natural vegetation. Blue is an unnatural colour in the sense that little in nature is blue, well-known species such as blue anemones, bluebells, and blueberries are actually closer to the violet. The colour is so unnatural that humans instinctively avoid blue food, and our appetites are diminished by blue light, presumably we associate it with mold. Moreover, our perception of colour is culturally conditioned, and in Western culture the colour blue has been associated with melancholy and gloom since the mid-1800s, an association referred to in a wide range of art from the past century in particular. Picasso had his blue period while struggling with depression (1901–04), Joni Mitchell released the album Blue (1971) about troubled love, Krzysztof Kieslowski's art film Three Colours: Blue (1993) shows a woman in deep emotional crisis, and in her poetry collection Bluets (2009), Maggie Nelson delicately explores existential themes. These examples lead us on to Blue's third, prominent distinctiveness: If you remain sitting in the amphitheatre that surrounds the sculpture for a while, you will discover tears flowing from the eyes of the doll's head at random intervals, tears that confirm what the title and colour insinuate: Blue is sad.

Are the tears emotional, theatrical, or are they political? Despite the fact that Heske has actively avoided positioning herself politically, she is a socially engaged artist, and the doll's head that was reborn in the thoroughly politicized 1970s is undoubtedly a child of her time. In several of Heske's earliest doll's head works, the doll can be interpreted as a symbol of the oppressed woman. Here she joins a larger movement in which a number of artists—prominent figures include Niki de Saint Phalle (b. 1930), Laurie Simmons (b. 1949) and Cindy Sherman (b. 1954)—take ownership of the doll as a symbol of femininity and process it artistically in a feminist perspective. In later doll’s head works, Heske's doll figure appears to a greater extent as a puppet or mask, shedding critical light on themes such as individuality in the age of mass media and vulnerability in the face of modern dogma. For Heske, the doll's head represents humankind. By constantly displacing and presenting the doll’s head in different periods of her artistic oeuvre, through decades where historical and cultural context is constantly changing, she allows the doll’s head to subtly reflect the human being and its era. In Heske's portrayal, the doll becomes an image of the human being contemplating what it means to be human.

Before we ponder why the doll's head cries, let's look at how it cries. The randomness that characterizes the flow of tears is not without significance and is an effect we recognize from earlier works. In the installation Raum der Stille, which Heske presented at the World Exposition in Hannover in 2000, spectators were invited into a room defined by total silence. At random intervals, and without warning, the silence was shattered by the sound of sudden, thundering rockslides. This fascination with suddenness, the artist herself explains, can be traced back to her childhood in Tafjord, a village in Western Norway known for experiencing frequent and entirely unpredictable rockslides from the mountains into the fjord. The most serious incident took place in 1934, when a landslide caused tidal waves around sixty-four metres high, destroying several surrounding villages and claiming forty lives. So as a child, Heske learned to respect the power of natural forces and perhaps also to fear their consequences—a lesson that is very relevant in a time when the climate crisis and ecological collapse pose serious existential threats. The colour blue indicates the sadness of the doll's head, but is it also the reason for its tears? Several elements in the sculpture’s environment, such as the "amphitheatre with a twist," which architecturally mirrors The Twist, harmonize well with the surroundings. However, with its distinct colour contrasting with the surrounding vegetation, Blue may evoke a sense of being out of place in nature, in the natural, much like the modern human being may feel alienated in a neoliberal society where technological solutions increasingly lead to less contact between people and perhaps even diminishing humanity.

By the way, it is not entirely accurate to say that we do not find blue in nature. After all, blue is what we see in the sky, in the sea, the vast expanses that surround us and that contain some of the most significant issues of our time. The sea is warming to previously unknown temperatures, engulfing those who try to cross it in search of a better life. Crises come suddenly at random intervals, just like the tears that flow down the cheeks of Blue. And resolving them demands the full extent of our humanity.

Text by art historian Ingrid Aagaard Holden, from the Sorbonne University in Paris, whose master's thesis focusses on the doll's head within Marianne Heske's body of work (2017).

-

01 Ståle Kyllingstad, Installation

-

02 Nils Aas, Consul Anders Sveaas, 1840-1917

-

03 Nico Widerberg, Time

-

04 Beate Juell, Stallion

-

05 Kristian Blystad, Playing horse

-

06 Bjarne Melgaard, Octopus

-

07 Kjell Nupen, Stille, Stille/Mediteraneo

-

08 Kjell Nupen, Mediteraneo

-

09 Edgar Ballo, Blå tulipan

-

10 Anne-Karin Furunes, Christen Sveaas

-

11 Olafur Eliasson, Viewing machine

-

12 Siri Bjerke, Mounts of the Samurai The Third Day

-

13 Fernando Botero, Female Torso

-

14 Tony Cragg, Articulated Column

The energy and shape of the sculpture easily give associations to the surrounding natural landscape, especially the water and the waterfall's fierce power/energy.

-

15 Fabrizio Plessi, Movimenti della Memoria

This installation is placed inside the Wood Pulp Mill

-

16 Elmgreen og Dragset, Forgotten Babies # 2

-

17 Marianne Heske, Homage to Leo the Lion

The sculpture is placed inside the Wood Pulp Mill

-

18 Shintaro Miyake, Welcome to our Planet

-

19 Kristin Günther, Hesten

The sculpture is placed inside the Wood Pulp Mill

-

20 Tony Cragg, I'm Alive

This sculpture, with the fitting title I’m Alive, at first glance looks like a powerful creature meandering forward.

-

21 Tony Cragg, Bent of mind

Bent of Mind looks as though it is constantly growing and changing. The two profiles, which make up the sculpture’s main motive, constantly change character as you move around the sculpture to see them from different angles.

-

22 Petroc Sesti, Energy-Matter-Space-Time

-

23 Magne Furuholmen, Hypnos Descending

-

24 Elmgreen og Dragset, Warm Regards

-

25 Anish Kapoor, S-Curve

-

26 Oldenburg og van Bruggen, Tumbling Tacks

-

27 Thomas Bayrle, Sternmotor Hochamt

You´ll find Sternmotor Hochamt inside the Furnace House, just outside The Wood Pulp Mill

-

28 Marc Quinn, All of Nature Flows Through Us

-

29 John Gerrard, Pulp Press (Kistefos)

-

30 Fredrik Raddum, Teddy - Beast of the Hedonic Treadmill

-

31 Fredrik Raddum, Catastrophic road Signs, Sun

-

32 Per Inge Bjørlo, Slektstrea, Genbanken

-

33 Phillip King, Free to Frolic

-

34 Jeppe Hein, Modified Social Benches Kistefos

-

35 Jeppe Hein, The Path to Silence

-

36 A Kassen, River Man

River Man by the artistic collective A Kassen took form as liquid bronze was poured directly into the waters of the Randselva river.

-

37 Ilya Kabakov, The Ball

The installation, with its location in the midst of nature, can be seen as a commentary on man's relationship with nature.

-

38 Tony Cragg, Castor & Pollux

With Castor & Pollux, Cragg takes a new and radical step in the development of the Rational Beings series. Raw muscle power and animal energy are just some of the things you experience in the encounter with this monumental work.

-

39 Lynda Benglis, Face Off

Benglis visited Kistefos and became inspired by the landscape and atmosphere of the site, Scandinavian mythology, and folklore. The sculpture can be seen as partly frozen waterfall, partly giant.

-

40 Yayoi Kusama, Shine of Life

-

41 Mark Manders, Silent Studio

-

42 Giuseppe Penone, Identity

-

43 Elmgreen & Dragset, Point of View, Part 1

-

44 Elmgreen & Dragset, Point of View, Part 2

-

45 Tony Oursler, Scat Skat Skatt

-

46 Lawrence Weiner, Stedsspesifikk skulptur

This sculpture is placed in two different locations in the park.

-

47 Magne Furuholmen, The Birthright

Text and letters have always been central as a pictorial element in Furuholmen's work. What happens if you deconstruct sentences, break them down into single words or put them together in new combinations?

-

48 Carol Bove, PASANASAP

-

49 Ida Ekblad, A DEADLY SLUMBER OF ALL FORCES

Ekblads sculpture is a fascinating hybrid of her artistic practices. The work is a sculptural collage made of fragments from her own paintings.

-

50 Pierre Huyghe, Variants

The work comprises artificial intelligence, 3D-scanned objects, living creatures and organisms, and offers something completely unique in the sculpture park.

-

51 Tone Vigeland, Skulptur I, 2022

Abstract in idiom, Sculpture I, 2022 almost seems like a distorted piece of jewellery as it changes expression every time you move around it.

-

52 Marianne Heske, Blue

-

53 Tatiana Trouvé, The Guardian

Tatiana Trouvé has drawn inspiration from the surroundings, history, and humans who shape Kistefos, painstakingly composing her sculptural objects as memorials of what was, and guardians of what is.

-

54 Tatiana Trouvé, Bench

The essence of Kistefos is encapsulated in the sculpture, inviting contemplation and reflection. The work allude to the workers’ community which was a defining feature of Kistefos until the mid-1950s, while also mirroring distinctively Norwegian values and ruminating on the universal human experience.

-

55 Kader Attia, Whistleblower

Kader Attia’s Whistleblower is a poignant reflection on the tension between natural elements and human-made objects. The inspiration for the work comes from the sound created when the wind passes through the neck of a bottle—a simple yet powerful symbol of the interaction between nature and culture.

-

56 Nairy Baghramian, Resting Arms

The sculpture, a highly abstracted portrait of primary joints in the body, was made in white Carrara marble and steel. By highlighting the vulnerability of the human form, Baghramian challenged the traditional connotations of durability and monumentality often associated with these sculptural materials.